A fishing beach community principal’s lament

Not enough value placed on formal education

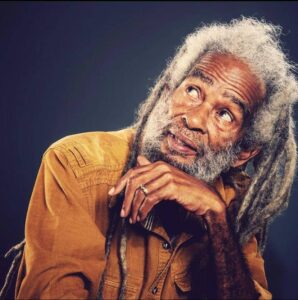

The limited value placed on formal education in Portland Cottage, a bustling fishing community in South Clarendon, is troubling to Dale Edwards.

“The effort is not there. You know the problems schools in a fishing community face. It is almost like ‘we can send the kids down by the fishing beach… when I’m in the mood I will send them [to school]’ that is one of the things,” Edwards, principal of Portland Cottage Primary, told the Jamaica Observer at the start of the new academic year on Monday.

“Sometimes we literally have to go to the homes to find students…it’s sort of a competition [between education and life in the fast lane]…they [some children] see where if they do certain things they can make more money than even you, so it’s not attractive anymore to them unless you have a parent that is literally pushing education. So for persons like this who feel that our job is just to send you to school, that’s it,” he said.

“A fisherman who has a boat will know that sooner or later my son will come and help me, and wi gone to sea. When I go down to the fishing beach, most of those I see are children that I taught. Some of these children, by the time they reach third form in high school, they stop, and these are the same people who later on have kids that we are teaching. They can’t teach their children so it’s a fight,” he explained.

In the meantime, Edwards said the school, in a bid to address the literacy challenges, is in the process of building out its library department which will also serve as a hub for students needing remedial help.

“We have children who have never gone to basic school, so we get some children who, by the time we start working with them, when they get to grade six, they are nowhere near where they should be, and so many primary schools are opting to get an infant department because at the basic schools you have to pay; so what parents do is they wait until it’s time for the children to enter school at the primary level,” he told the Observer.

Determined to address the literacy issues from all angles, Edwards, himself a past student of Portland Cottage Primary, said his vision is to see an infant school department constructed on the school grounds to enable educators to expose young children to the basics before they enter the primary level.

Another sore point which, he said, the school is struggling to address is the difficulty in getting children who teachers suspect have learning disabilities screened.

“That’s another problem. When we make the referrals to have the children screened, sometimes the parents don’t have the money to go to May Pen, and a lot of times when the [education] ministry looks at the exam results they say to the teachers do this and do that, but there are many other factors,” Edwards lamented.

Edwards had taken the Observer on a tour of the school, which, despite opening to its full complement of teachers, was still under repair, although being on the Ministry of Education’s priority work list in the aftermath of Hurricane Beryl which struck sections of the south coast on July 3. More than half of the school’s population are beneficiaries of the Programme for Advancement Through Health and Education.

In late August, the ministry indicated that it had accelerated its efforts to repair schools in time for the September 2 reopening. Of the island’s 1,009 public schools, 352 were damaged by the hurricane. Up to last week, 200 schools were still without electricity supply, according to Education Minister Fayval Williams.